‘Two Worlds’ proposes, then, two different modes of being in the world,

linked to two types of fortune – luck or monetary, both covered by the English

word fortune. Here cultural difference is registered – one world where the

caprice of the gods organizes and determines life’s meaning, and one world

where even the internal sense of self is measured in terms of hard cash

equivalent. And what is that internal self -

something pre-articulated, the inside as pure externality indeed.

What Adorno and Horkheimer called ‘the system which is uniform as a whole

and in every part’ still persists and, despite well broadcast assertions

of diversity and choice, in this world too ‘all the living units crystallise

into well-organised complexes’. Indeed the monopolistic tendency is even

more pronounced nowadays, when, for example, in the United States media

concentration is far greater than ever before - a huge world market divided

up between the ‘big ten’ media conglomerates that have billion-dollar interests

in publishing, television, film, video and radio, music, theme-parks, internet

and sports. Concentrated ownership across these areas makes it so much easier

to cross-promote products, i.e. to produce material in multiple formats,

as in the Disney animation film that becomes video, theme-park attraction,

book, in magazines, pop hit, toy and accessories, and McDonald’s or Burger

King ‘freebie’. It all locks together tightly and forms an unavoidable bulk.

This is a world of exhausted internationalised formats, where repetition

is compulsive, as Pop Idol, Big Brother 2, 3 and 4

and Celebrity Big Brother, or Celebrity Survivor,

or another so called Reality TV show and/or quiz show format replicates

around the world. Boredom inhabits this process as a permanent threat, and

so hopes are high for short memories as the next re-recycling comes round,

and celebrities rise and fall, to give the illusion that something is really

happening, when really everything in essence stays the same: the business

as usual of the expropriation of surplus-value. The culture industry has

perfected techniques of substitution in representation. Reality TV shows

- of which in the UK and the US, at least,

there are many varieties, including those which include competition as part

of their format - dramatise non-lives, re-inforcing

the banality of life and delighting in human tensions. There is a myth of

uncovering talent, or specialty in some, such as Pop Idol, but the

shows work best when mediating failure, mediocrity or hatred. These shows

parody representation, by paralleling all the mechanisms of democratic form

- through voting - albeit it at very high

telephone call costs - , and occupying the

public sphere, in newspaper discussion and free exchange amongst individuals

on chat groups and elsewhere. The shows expose the very processes of how

spectacular fame is manufactured, and so seem to have nothing to hide. This

seemingly total exposure lays bare a realm of system-rational goals which

are values, and the values are wealth and celebrity. These are utterly unchallengeable

assets, which are ‘democratic’ simply because everyone is supposed to want

them. They express the general will - which means that the property system

is not only unaffected. It is vaunted. The more the gap is widened between

them and you, the more arresting it is. The more arresting it is, the more

its hidden structures of ownership are reinforced, the wider it spreads.

Representation short-circuits, marking only the place of the commodity speaking

for itself or through its audiences turned advocates.

The standardization of culture is linked to industrial capitalist forms

of manufacture, and so, as that form became everywhere the dominant form,

in its trail followed a global standardization of cultural forms. The dying

peasant in China – or at least the peasant’s cousin, the factory worker

- is exposed eventually to the same images

and sounds. The extension of the standardised domain brings with it the

promise of pleasures that are rarely fulfilled but keep people hoping and

holding on to the edge of the abyss, instead of struggling out of it. But

there is a flip-side. From this tendency of the commodity form to universalise

itself, a global working class is forged, with common reference points.

A common language, of products and advertising, of work processes and management-speak,

of establishment political rhetoric world-wide, is shared – a universally

understood language emerges. Languages -

even individual words - can be made to say

very different things, depending on the spin. Subversion too has the chance

to be universally understood, and that means universally reiterated to potentially

devastating effect. This is where art and politics conjoin. Or, better,

cultural practice is recast. A certain type of ventriloquistic critical

cultural practice emerges, in recognition of the overly loquacious commodity.

In a letter to Gershom Scholem in August 1935, Benjamin set redemptive

quoting at the heart of his method, a salvaging of scraps, the penetrant

but trivial flotsam of our daily lives, and, in redeploying them, re-articulate

them. He recorded his ‘attempt to hold the image of history in the most

unprepossessing fixations of being, so to speak, the scraps of being’. The

process of ‘globalisation’ has produced its antithesis, a globalised resistance

- which might be resistance to globalisation

or, more specifically, resistance to world capitalism on a world scale.

This global fightback established or occupied channels of information, discussion,

distribution, commentary and critique. Here is another world of cultural

activity – epitomised in anti-capitalist activism, and much of which is

instinctively or consciously based on avant-gardist theories and practices

(e.g. montage, detournement), processes that previously resonated most forcefully

at moments of revolutionary upheaval, i.e. the 1920s and 1960s. This new

wave of practice is manifested both digitally through various types of 'net-activism'

and in old-school styles (e.g. 'Billboard Liberation', fly-posting, graffiti).

It works specifically on representation in relation to property relations.

Such practice might be fruitfully considered in relation to Benjamin's concept

of the 'new barbarism' – here like then a kind of squatting of the enemy's

methods, tools and modes of address. Benjamin argued that 'impoverished

experience' can be overpowered only if the fact of poverty is made into

the underpinning of a political strategy of a ‘new barbarism’ that corresponds

faithfully to the new realities of the constellation of Masse and

Technik. His examples included Brecht, Scheerbart, Adolf Loos, Cubists,

Paul Klee and early Disney.

Quoting from Benjamin’s vignette ‘The Destructive Character’, Hardt and

Negri write of how the poverty of experience obliges the barbarian to begin

anew, that the ‘new barbarian ‘sees nothing permanent. But for this very

reason he sees ways everywhere’. For them, the ‘new barbarians’ ruin the

old order through affirmative violence. Hardt and Negri argue, then, for

the progressive nature of barbarism following the collapse of the Soviet

Union. A migrant barbarian multitude – former ‘productive cadres’ who desert

socialist discipline and bureaucracy in a bid for freedom. Its barbarism

manifests in modes of life - their bodies transform and mutate to create

new posthuman bodies, fluid both in sexuality and gender ascription, cyborgish

and simian, bodies that are ‘completely incapable of submitting to command’,

and ‘incapable of adapting to family life, to factory discipline, to the

regulations of a traditional sex life’. There is a technological supplement

to this. Hardt and Negri write: ‘The contemporary form of exodus and the

new barbarian life demand that tools become poietic prostheses, liberating

us from the conditions of modern humanity.’ And these protheses are, according

to Hardt/Negri, those of the ‘plastic and fluid terrain of the new communicative,

biological, and mechanical technologies.’

But Hardt and Negri’s Benjaminian barbarian is misconceived. This fluidity

and self-modification misapprehends Benjamin’s ‘positive concept of barbarism’,

for this relates to art’s producers and consumers and is strategic and negational

– that is to say it operates in contradictory relation to the points of

tension, rather than setting up a parallel utopian existence. Benjamin’s

positive concept of barbarism has less to do with an effortless prosthetic

use of technologies to modify bodies, flowing in the direction of capital’s

own unfolding and post-human dreams of immortality. It has more to do with

a scornful appropriation of technologies and the techniques they suggest

for strategic purposes of representation. The attempt is to make the speaking

commodity condemn itself, in its own language and via an over-exposure that

represents all too well the punishing barbarism of our world - as did John

Heartfield too in his photomontages. Not over-dramatically, but through

form, texture, choice phrases and a suspicion of bombastic Realism, both

in its socialist form and in today’s New Capitalist Realism - with its glamour,

mediation, pop reference - that has accompanied

the former so-called socialist parties’ turn to what they call the New Realism.

It makes little sense to speak of today’s newly barbaric practices - which

happen both locally on any street corner or globally via the world wide

web, frequently anonymously, eschewing the personal mark of the creator

- as either art, on the one hand, or politics,

on the other. They are both. And they are also a response to the cheapening

of technologies and new forms of reproduction and distribution, as well

as a response to the world-wide marketing of signs, and, along with them,

the values that they attempt to enforce globally. At their core is a challenge

to property relations and the division of labour, for they overcome the

notion of artist as profession. They make manifest the struggle to link

representation to the right to alter property relations. The tendency of

the commodity form is to universalise itself, presenting us then with shared

experiences, shared languages, shared experience of class exploitation.

In this context, today's impoverished experience is taken to task and re-animated

- en masse and technically - by 'newly barbaric' strategies of occupation

- and occupation means not relinquishing the ground. .In that context the

struggle over signs is a type of Esperanto, internationally experienced

and internationally understood. It has its moments of irony and subtlety

- subvertisements, net activism spoofs, ironically positioned billboard

liberation front activities - all of these anti-culture struggles against

the clutter of commercial signs in the environment. The copyrighting and

commodification of language as property is most ludicrously expressed in

the propaganda of the Brand Names Education Foundation, whose

stated mission is:

Michael Jackson in East Berlin

Berlin

beer advert at the time of Christo’s ‘Reichstag wrapping’

Berlin

beer advert at the time of Christo’s ‘Reichstag wrapping’ An

Instant Coffee Jar foil

An

Instant Coffee Jar foil ‘I

can’t believe it’s not butter’ brand of margarine

‘I

can’t believe it’s not butter’ brand of margarine ‘Deliciously

flavoured rice’

‘Deliciously

flavoured rice’ Themed

spaghetti tins

Themed

spaghetti tins Beer

advert on Camden High Street, London

Beer

advert on Camden High Street, London The

rich aroma is moments away….instant coffee foil

The

rich aroma is moments away….instant coffee foil ‘Bliss’

and ‘sublime’ sauces

‘Bliss’

and ‘sublime’ sauces ‘Cool’

crisps

‘Cool’

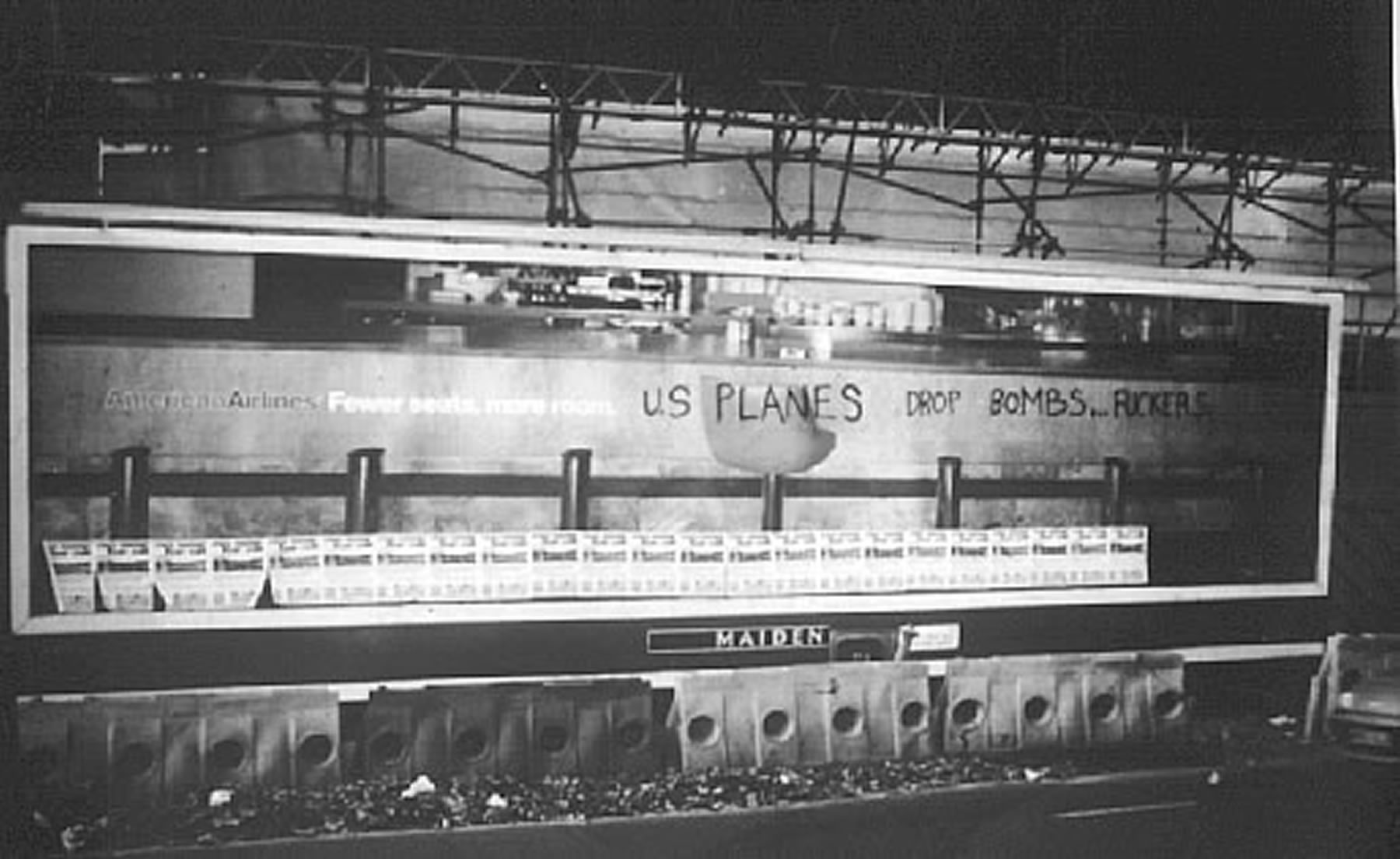

crisps American

Airlines advert – graffitied with US planes drop bombs …..fuckers.

American

Airlines advert – graffitied with US planes drop bombs …..fuckers.