FROGS

A talk given at the Chisenhale Gallery, in response to Simon Martin's Untitled (2008)

A book of natural history, begun in 1774, states the following in its preface.

NATURAL HISTORY, considered in its utmost extent, comprehends two objects: First, that of discovering, ascertaining, and naming all the various productions of Nature; secondly, that of describing the properties, manners, and relations, which they bear to us, and to each other. The first, which is the most difficult part of the science, is systematical, dry, mechanical, and incomplete. The second is more amusing — exhibits new pictures to the imagination, and improves our relish for existence, by widening the prospect of Nature around us.The book, an 8-volume work by the poet Oliver Goldsmith, is titled, aptly enough for the current context, An History of the Earth and Animated Nature. It is a Romantic work of scholarship. Goldsmith decided that the best way to depict the wonders of the natural world was ‘to write from our own feelings and to imitate nature’. In his book nature already described is here re-described through observation, heavily coloured by identification and empathy. Notions of the sublime cannot be far away. If the first object of natural history is the apprehension of nature and its knowing, then the second destabilises this, penetrates further into a realm in order to realise it is not known, or not fully known or known in new and ever new ways, within the ever-widened prospect. It is the natural object remade in thought and imagination.

The title of Goldsmith’s book relays something about a Romantic stance towards Nature. The nature he writes of is animate, which at its simplest means that he wishes only to write of nature that can be described as alive, properly alive – as, for example, are animals. But beyond that he also indicates his approach: that nature is precisely something spirited, as lively and interconnected and multiply related, sometimes through enmity, sometimes solidarity, across its chain of being. Animated nature is historical, changing over time, dynamic, and all the vital elements of the universe, from the highest, the human, to the lowest, the insects, are animated by spirit, which is to suggest – as Darwin makes clearer later – all of nature is unified by what Coleridge in 1796 called ‘the one Life within us and abroad’. Nature is us and we perceive parts of ourselves reflected in all its elements.

I mention Goldsmith’s animated nature, not just because of the coincidence of vocabulary, but because his stance proposes something of relevance to the current frog, the one in the other room, a digital confection in a seeming 3D space, who occasionally makes smallish movements, and who is intermittently replaced by flat white words on black. The strawberry poison dart frog of the natural world has been discovered and named. The mechanical, dry and systematical work of labelling is done. That frog is then released into another world, the one of representation and imagination, one that I would describe as a world of second nature. It finds itself here, in this particular case, a mediation of a mediation of a mediation etc, a digital reconstruction of a photograph, parsed through a drawing parsed through photography, and so on. Now before us, stands the fictional frog, an estimation of a frog confected out of pixels, its image is reliant upon the mechanical eye of the camera that ‘saw’ the original image and translated it though technique and technology into an illusory three-dimensional frog. The frog becomes a work of natural history, in Goldsmith’s sense, which is to say it becomes not just named and known as an element of nature, but also reflected upon and re-made. Re-described digitally, from varying angles, his manners and properties are evaluated and emulated, but more than that the frog is a frog for us, a frog of our world, not the secretive and impenetrable realm of nature, but still he is also a mystery, a hybrid, a conundrum, a sublime object, impossible and actual at one and the same time. The frog before us is, as Goldsmith puts it, ‘amusing’ and, in high definition, it is the exhibition of a new picture for the imagination, a demonstration of the widened prospect of Nature around us.

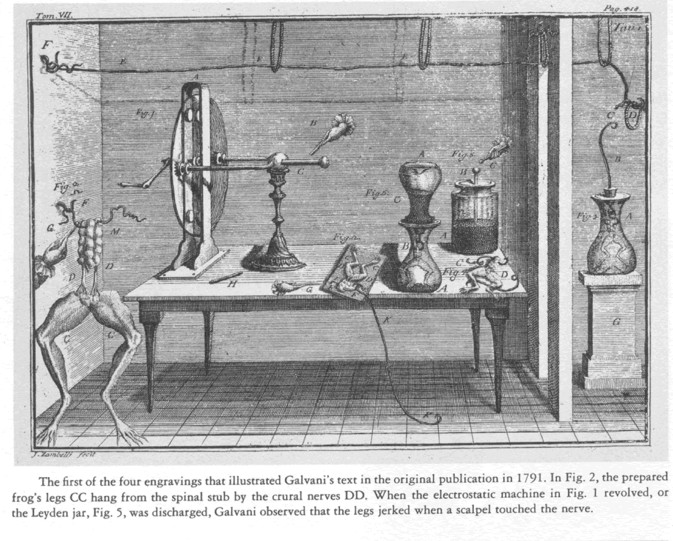

Only a few years after Goldsmith’s first investigations into animate nature in 1774, a frog’s jerky legs became a celebrated event, indeed it appeared as a new type of magic, a reanimation, even as it was also a scientific sensation. Luigi Galvani sent an electrical charge through the legs of a dead frog. They twitched, as if alive. Galvani had found biological, animal electricity. Our nerve cells and our muscles twitch electrically. We generate bio-electricity. Organic tissue generates electricity. The nervous system conveys information electrically. Such a new recognition of the self found fictional form famously in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, with the monster re-animated by the sparks of electricity. Life is electricity, for Galvani. Animation is electricity. Frogs and humans alike are electrical. There is ‘one Life within us and abroad’.

All this is to say, romantically, when we see the frog we also see inside ourselves, inside our imagination of frogs and what they mean for us. Indeed, to push it further, we could say – a la the Romantics – we see ourselves in the frog. Its throat expands and contracts constantly, just as our own breathing and rising and falling chests become noticeable to us, standing there, in silence, watching. This is animate nature, so are we. It has all the signs of life. Life has been breathed into it, but, in this case, not by God, and not as a product of nature, rather by the power of illusion. It is animated by animation. The animation here is constant in the breathing and it is intermittent in the jerks and shudders of the frog’s legs. This animation – like all animations – is made of a combination of incremental moves and abrupt moves: the shifts from frame to frame that produce the illusion of mobility and the jerks of the legs, the leap out of the frame, the unexpected shifts in the point of view.

The frog’s shudder is a dramatisation or an analogue of our own, if we go by the thoughts of Adorno, for whom the shudder represents the very principle of life itself, barely findable today but sometimes emergent in the experience of art. Adorno thought that mimesis - the exchange of properties, dynamic intersubjectivity, assimilation into the self of otherness - was an essential component of experience, simultaneously terrifying and ecstatically anti-egoistic. It had been violently and disastrously excluded by modern rational society. At moments in our ‘damaged lives’ – particularly moments of true aesthetic encounter – genuine experience still occurred, and when it did, it did so with a shudder.

In the end, aesthetic behaviour could be defined as the ability to shudder, and so goose pimples are the first aesthetic image. What is later called subjectivity, because it frees itself from the blind terror of the shudder, is at the same time its very unfolding; nothing lives in the subject other than its shudder, the reaction to the total spell. And only the subject’s shudder can transcend that spell. Consciousness without the shudder is fully reified. Shudder, in which subjectivity stirs without existing, is the sense of being touched by an other. The aesthetic mode of behaviour assimilates itself to it instead of subduing it.Cinemas and fairgrounds have long been the places where people go to reproduce the shudder synthetically. Film, from its earliest days, and none type more so than animation, especially in its stop motion variety, used its technological pre-disposition to play with the shudder – of its object and its viewing subjects. The shudder comes from the realm of the uncanny. Animator J. Stuart Blackton, for example, in 1907 made a ‘one turn, one picture’ movie called The Haunted Hotel. The viewer watches as a building begins to wobble. Then, a cut to the inside shows objects moving of their own volition. A knife slices bread on the table, tea pours itself and sugar cubes hop into a cup. The room tips to one side and furniture slides. Finally, the room starts spinning. Blackton’s home is spooky and overly possessed of spirit. And if uncanny animated objects are of interest, then perhaps it is necessary to mention the work of Ladislas Starewicz. In the first decade of the twentieth century he developed stop-motion animation, through re-animating dead nature He made articulated puppets out of the corpses of beetles and frogs * and moved them by unseen wires, also filming the motion blur to make the animation more photo-real. This is a still from The Insects’ Christmas from 1913. Brought back to life and moved at will by the animator, dead nature remade participated in kitsch stories and fables of political rule.

Some twenty years later, a more benign version of the shudder that brings the dead to life, the immobile into mobility, would appear in cel cartoons. Alarm clocks, sofas or footstools with cheeky smiles and flexible body parts are the distorted twins of viewers. They mock us, as do too - in uncanny moments - our other ‘immaterial doubles’, the shadow and the mirror image, those entities produced by our bodies but not quite identical to them, disquieting, unfamiliar and, yet, never better known. In its benign forms, as in Disney’s lively furniture, humanised technology and objectified humans, it struck Walter Benjamin as part of a miraculous existence promoted in cartoons, which - redemptively - infuses with magical impulses an alienating existence adrift amongst nature and second nature alike.

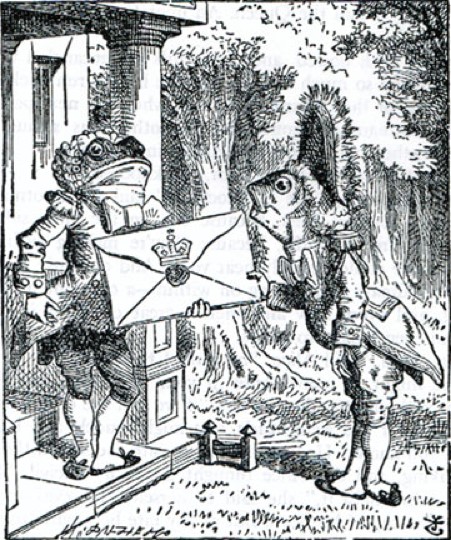

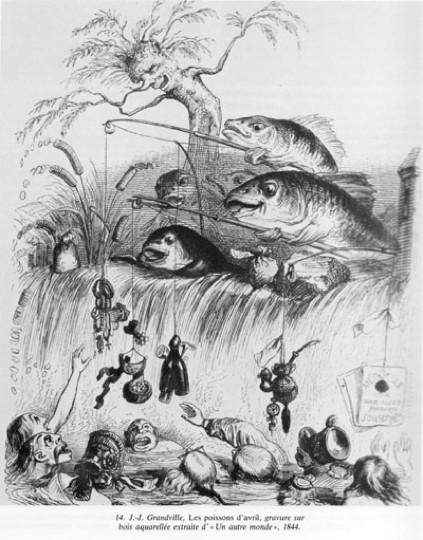

The animated frog here in the other room, more electrical than most, confronts us with its jerks. Its jerking, a leg outstretched suddenly, a leap, a shudder, is the very principle of animation and is a sign for the principle of animation. Movement, motivated by its being a frog – frogs kick out their legs – is here brought into being by the animator. Galvani discovered and then emulated an innate principle of electrical impulse. He opened up nature in dissection. He found something within it and he found a technique of imitation, which revealed something about the actuality of life. Here, this shudder, this jerking, is once again an imitation. It is a technological confection, not a natural effect – and yet, like Galvani before it, it opens up the animation for us, as animated entities at the other end of the chain of being. It is a movement made by the animator, attributed to the frog, witnessed by us – it has passed through nature, but is an effect of culture, replete with motion blur, to make it seem more photoreal, though not necessarily more real. The animation makes second nature out of nature. That this is an issue for the animation in the other room is underlined by its intertitles with their by-the-way evocation of brands and gadgets, fashionable and faded materials, must-have items and retro stuff that has been in and then out and then in fashion, in short all the flora and fauna of modern logo-soaked and connotation-heavy life. The combination of the confected frog, decorated in colours to die for, and the style-hyperconscious paragraphs makes for an up-dated version of the parodic sentiments in Grandville’s caricatures of the 1840s. Grandville’s caprices confuse nature and fashion items, people and commodities, the animal world and the human world. Here in the careful detailing of designer goods and de rigueur activities is something akin to Grandville’s skits on the overliveliness of those new worldlings, commodities, and the seeming victories of transient fashion over eternal nature: flowers flaneuring in furs and gemstones, a cast-iron balcony around the planet Saturn, perfectly placed for night-time gallivanting, the wheel of fashion, an illustration of fashion’s endless and conformist push, its mechanical ahumanism that would like to present itself as the most natural rhythm in the world. Indeed, Grandville’s favourite animals were said to be frogs – he kept a pet one on his drawing table – and he used them variously in his sketches to represent children, clowns, or victims of murder. It was his frogs of civilization that were borrowed by Tenniel for his frog footman in Alice in Wonderland.

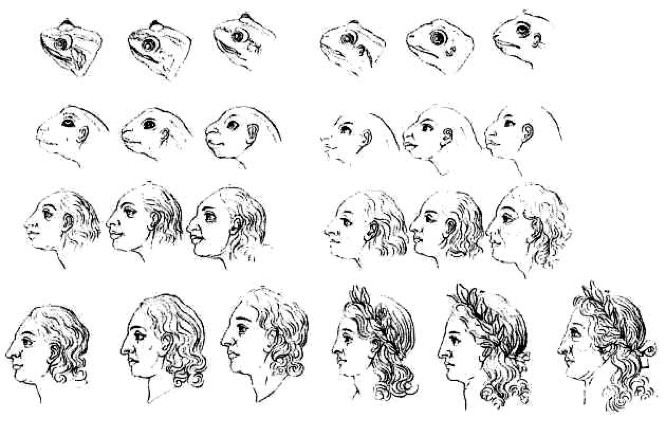

Grandville, incidentally, was a follower of the physiognomist Lavater and he illustrated Lavater’s thesis of the chain of relationship from humans to animals in a sketch ‘Man descending towards the brute’, for the book Heads of Men and Animals Compared. It showed a sequence of heads turning in small increments from that of a man to that of frog. It was based on images commissioned by Lavater in the 1770s and titled ‘From the Frog to the Poet Apollo’.

A metamorphosis takes place over 24 – note film enthusiasts – 24 slightly varying images. In small gradations the vast gulf between humans and animals is asserted and bridged simultaneously in visual form. The incremental and the abrupt meet again. Simultaneously, of course, the very principle of animation is being outlined, in the move from frog head to human head and back again: through conceptualization, nature is redrawn, new associations made between the species. Second nature evolves.

That this chain precisely is a potent one is indicated by its presence in those oldest stories that, incidentally, have often been animated – fairy tales, in which the frog once kissed becomes a prince. The form moves from the lowest to the highest, animated by the power of love – or, as in the Grimm Brothers’ and others’ version, through a violent act, a sudden movement, a flinging of the frog against the wall by the Princess, who cannot bear to succumb to his ugly form. Such metamorphosis is both subject and synecdoche of animation, for animation is comprised of morphing. The metamorphosis of frog to human as envisaged by the physiognomists was the impulse for the drawn gestures in fellow Swiss Rodolphe Töpffer’s little graphic novels of continuous strips, with their characters, Mr Cryptogam and Vieux-Bois and others, in whimsical, nonsensical plots. His transformations of an object, for example, a face, are credited with inventing the genre of bandes dessinées in the mid-nineteenth century, and they were first passed around Europe by the enthusiast Goethe, poet and naturalist, who recognized in them their conjoined quality of movement and imitation. A letter to Töpffer describing Goethe’s response upon first seeing the caricatures of Mr Cryptogame in 1831, notes the following:

M. de Goethe found your nature-lover very amusing, and what seemed to strike him most, apart from the originality of the drawings, was your talent for exhausting a subject, for getting the most out of it, for example, when all the inhabitants of the vessel down to the furniture follow the rotatory movements of Cryptogame, when everything freezes and unfreezes as if it were in the spirit of imitation’.Goethe is referring specifically to a scene in which the hero runs around a boat, chased by all the others onboard, until he leaps overboard, and then is followed by all the rest, the crew, the animals, the rats, the furniture and, finally, the ship itself whirls on the page. Goethe recognised the key impulse in caricature and animation: that movement between frames is matched by movement between the imaged objects – the mutual mimetic drive, which results in footstools with personality or human-animal hybrids or moons and pick nicks alike made of cheese-plasticine. For Goethe, indeed, it was as if the complex curlicues and spirals of his Urpflanze theory – the assumption that all life emerges from one species - which is a precursor to the theory of evolution, was represented in Töpffer’s drawings of identity and variation.

The animators of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs used Töpffer-like variations in the scene the dwarfs crowded at the end of Snow White’s bed, their noses drooped over the bedstead, each face a little different from the others, but also all echoed in the surrounding features and fixtures of the cottage. The differences between it all are small and that is wherein their significance lies. Such small differences, such tiny movements are the matter of animation. The movement is in the image – it moves – and in the action of drawing on the real, its caricaturing, its morphing of the real into the drawn, fictional, re-interpreted, subjectified world. I have tried to point out some ways in which ideas of nature as a chain of being, as animate, might fruitfully find their way into ideas of nature as animated by human imagination – be that in a natural history sensitive to mimesis and reflection across species – and beyond – or be that in its redrawing in caricature or cartoon. I want to return after this more or less historical exegesis to the frog in the other room, this drawn frog whose existence in second nature I have already described and whose presence in the present I want to explore a little, in the context less of a benign Romantic theory of mimesis and cross-species fascination between subjects – and more in the context of technical objectivism.

This nature, in the other room, the frog, that is no longer one, and never was, but is rather an emulation of one existing in an illusory three-dimensional space and a constructed time, and admidst motivated and unmotivated sounds, which are all, of course, alike effects of post-production, croaks its fake life in high definition. Such an image, blown up on a large screen, is not unfamiliar to us. Indeed it takes its place alongside many others that are somewhat like it, ones that are more directly tied to the world of commodities, commodified images. Its second nature has become quite firmly a part of ours. I am thinking of the in-store demonstration films for LCD and plasma screens, fantastical images of nature as second nature, as pre-texts or stimuli to buy. The natural sublime of tropical forests, exotic underwater and the jungle presents itself as most suitable for selling TV’s updated machineries of reverie. As does the literally sublime – high, exalted, under the lintel - aerial pans across skies and mountainous landscapes. High technology conjures up high nature to sell itself. This nature sublime cried out for the machinery’s remarkable vividness in modelling 3D, its deftness at displaying supersaturated colours, the ability to display smooth movement and the inviting capacity to immobilise the image, as the preset ‘picture freeze’ function suggests, in order to hold onto the moment of wonder.

In the 1960s Walt Disney helped promote, and therefore sell, colour TV in the United States through the show Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, broadcast by the NBC network because its parent company, RCA, manufactured colour TV sets. Now high definition TVs get a fillip through a series such as Art Wolfe’s Travels to the Edge, moving and still shots in high definition of the natural world, from ants to tribes to zebras. Partly-financed by Canon Wolfe’s TV programme also offers photographic tips and techniques, and so boosts too sales of high-end digital cameras. Wolfe is a leading nature photographer in the US – here is an image made for National Geographic magazine. Indeed it has been claimed that his style developed over the last 30 years has helped to shape the standard look of US nature photography, and can now be found ubiquitously on calendars and mouse mats. The lighting is Romantic, the colour is saturated, the focus is selective, the background blurred, the subject appealing ‘biophillically’, gazing out of the image with an arresting glint in the eye, the action is bloodless. In fact its look resembles entirely the fictional frog in the other room, who may, for all I know, have once been a photograph by Wolfe, who put out a book of frog photographs in 1997 – very similar in style to the one that was found the following year and that stimulated or animated into being the frog who now has taken shape in the other room.

The new digital TV displays and digital cameras are touted for their ever higher-definition lifelikeness, but it is in the process of seeking higher definition that the need to enhance or undermine the inadequate real comes in, and technical fixes offer themselves so readily. Wolfe, of course, a pioneer in the use of digital photography in nature, was enmeshed in a controversy over image manipulation in the 1990s. The Denver Post and Seattle Post- Intelligencer reported that Wolfe had rearranged and replicated herds of elephants and zebras in his photo book from 1994, Migrations, and that a third of the images were digitally altered. Single animals were copied and pasted elsewhere in the image to bulk out herds, to make aesthetically pleasing arrangements of nature, quite apart from the usual variety of colour and contrast tweaks so easily available to digital photography. Nowadays Wolfe has to be more vocal about the use of manipulation in his digital practice. He naturalises it, stating, for example, ‘Typically, what we do with any image when it’s in digital format is to boost the contrast a little bit and saturate the color on everything. They always look a little better to me. That’s the process we do with every digital image, and that’s all.’ And if that is not enough, the other get-out clause is to say, as he has of Migrations, it is not science, but art, which means it need not partake of truth to life. Art Wolfe’s latest images of nature, from ‘Travels to the Edge’, are mobile and shot in high definition, and can be bought from Getty Images, searchable by price, type, technique, subject, filters, viewpoint, style, location. This is an extended technique of naming, knowing, classifying and ordering the natural world.

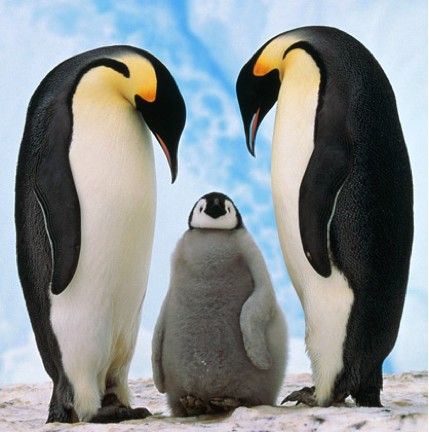

The digital realm knows nature in new ways and makes it anew. Take, for example, the push in commercial digital animation to parade studios’ technical abilities through computerised renditions of the natural sublime. Recent computerised animation has directed its techniques to simulate the spectacle of wild nature – not unlike of course the wielding of oil paint to simulate brutal nature in Caspar David Friedrich’s Sea of Ice some 160 years ago, just more elaborate, even more machinic. Countless SIGGRAPH papers testify year after year to efforts to model the wind-driven accumulation of snow, the complex fluid dynamics of floods, tsunamis and turbulent splashing water, ripples on the surface of ice, the vortices of superstorms. Not just the look of nature but also its behaviours re recreated. The anti-physics that was originally intrinsic to cartoon worlds cedes way in new uses of animation for physical simulation. Once effective techniques of nature simulation have been devised they translate commercially into dramas whose plots act as segment-by-segment pretext for illusion showcasing. So recent animations have been set in oceans or amidst the frozen waters of icy, snowy landscapes, these zones perhaps the backdrop or envelope for overlively dancing penguins, incarcerated clownfish or dolphins choreographed underwater. Examples include child-oriented animations such as Ice Age, Ice Age: The Meltdown, Happy Feet – as well as ostensibly real-action disaster films such as The Day After Tomorrow, which renders digitally the turbulent, unstoppable waters of the floods as well as, freezing fluidity and immobilising the whole Northern hemisphere under a sheet of ice. The Day After Tomorrow presents scenes of a New York immobilised under snow and ice after a ‘superstorm’ causes rapid worldwide climate change. Other eco-apocalypse films came in its wake. It is the spectacle of absolute devastation that concentrates filmmakers’ efforts and captures audiences’ imaginations. The pleasure of the films lies in their rendering of the drama of catastrophe. The film scenarios are dependent on technological wizardry – making these depictions of nature’s revenge celluloid versions of Adorno’s thesis of a ‘dialectic of enlightenment’, a forceful return of the mythical via an inadequately integrated technical. The scenarios depict nature crushing technology and its masters, the humans, through a technically rendered spectacle that aims to be magically imperceptible. The logical destination of photorealistic modelling is to prove itself – which is to say, to make its fictions invisible - in the photoreal context of live-action.

There are many efforts to deliver computerised illusions of turbulent nature – moving pictures of movements so grand they overawe us in the cinema or in our domestic spaces – there are also smaller efforts to harness the power of computing to execute animation’s most basic gesture – the illusion of movement out of stillness. There are various ways to animate still photography. One way in which this is done is a technique whereby a foreground figure is excerpted from the photograph and disassociated from the background and then, via some sort of computer trickery involving focus and simulated depth of field, a fake parallax is effectively offered. Once this is achieved, the camera pans in across the field now rendered ‘more lifelike’. This is akin to another type of animation of still photography, pioneered in documentary film. This has been popularised and made available in image-processing packages, such as iPhoto and iMovie and Premiere. It is called the Ken Burns Effect after the influential US documentary filmmaker. In its popularly available version an automated function allows any photograph to be slow panned and swooped across as if it were a 3-D realm.

In these computer techniques, movement is faked where stillness was. Animation is thrust on the past technically. On the one hand, film is broken down into still frames for computer processing. Its movement is arrested in order to be built up again digitally. On the other hand, photography’s stillness is overridden by the panning camera, in order that a semblance of life be impelled on the past. Freezing film into frames that can be digitally manipulated is to make experience, the experience traced in celluloid, pseudo. Documentary – as the original film footage or as the still photograph explored technically – is no longer the archival trace of historical activity, but rather an activity that is about its own very process of arrested or faked flurry.

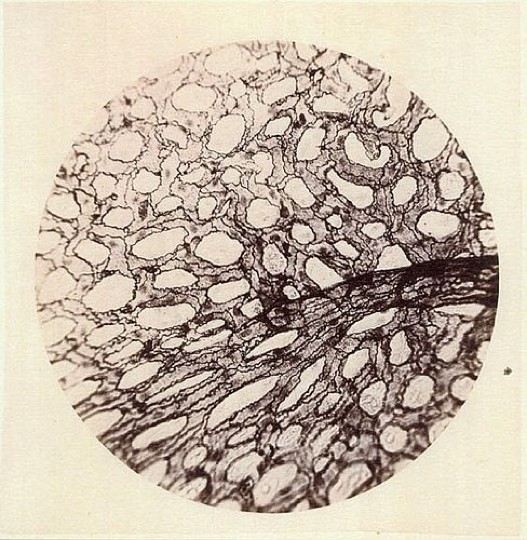

Which returns us to the frog and his motion blur. This flat photograph made into a three dimensional space, a slice of cosmos that never was, except in as much as it is for us now. Our frog is trapped there. It moves, but it never goes anywhere. Or it disappears, only to return again. The animation is a trap. It traps the frog. It traps us in front of it. This is indeed the ‘different nature’, the ‘other nature’, that Walter Benjamin claimed was brought forth by the camera. His reference was the photography of Karl Blossfeldt. The glass lens of the camera produces the world anew, reactivating or re-dynamising the relationship between seer and seen, through the deployment of close-up lens technologies. For Benjamin, such photographic images of the natural world, scientific contributions that also showed just how mysterious the everyday could be. Blossfeldt’s photographs reveal strange analogies, ones that intermingle natural and artefactual forms and dramatise the action of the camera on nature. That is to say, these are images of what Walter Benjamin called ‘different nature’, of a nature confronted by creative human labour, self-constituting and expressing a worldview, kinship and protection, in short human civilisation: ancient columns in horse willow, a bishop’s crosier in the ostrich fern, totem poles in tenfold enlargements of chestnut and maple shoots, and gothic tracery in the fuller’s thistle. As such the images are evidence that nature too can be a realm of human transformation in co-ordination with technology and thought. In ‘art’ as in ‘science’, for so too does microscopy photography in its magnification of the structure of cell tissue. For Walter Benjamin the camera reveals aspects, indeed whole worlds of images, ‘physiognomic aspects, image worlds, which dwell in the smallest things’, that have previously never been seen before – except perhaps in dreams. See here Joseph Janvier Woodward’s photomicrograph of the arteries and capillaries of a frog, from 1871.

The camera discloses through its barrage of effects that assault the unquestioned coherence of actuality: slow motion and enlargement, for example. It routes vision through the machine and so detaches humans from their conscious, or habitual modes of seeing. It ‘reveals the secret’ and so dredges the world up from unconsciousness into being known. Technology and magic dissolve into each other or rather show themselves to be aspects of the same, as Benjamin repeatedly insisted.

I think that what the frog in the other rooms brings back is a different nature, one so thoroughly imbued with technology and with culture it is indisputable that it is a frog of second nature and as such a relative of all the other frogs from the Frog Prince to Art Wolfe’s poster-frogs. But it is also a non-frog on a non-leaf, in a non-space. All this looking – all that technique of natural history that Goldsmith evoked - sees precisely nothing and everything, precisely in high definition.