Phenomenology of One Size Fits All: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Frank Zappa

Zappanale #14

by Ben Watson

Friday 13.00 25 July 2003, Kamp Theater, Bad Doberan organised by the Arf Society

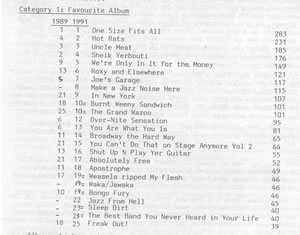

One Size Fits All is a favourite album for Zappa fans. In 1989 and 1991, T'Mershi Duween, the Zappa fanzine published in Sheffield, England, ran readers' polls. Both times One Size Fits All was voted "favourite album". This is how the results looked in issue #23.

It was inevitable that Hot Rats would score high. It was the most successful record Zappa ever had in the UK, reaching number 9 in the album sales charts in 1970. As he said in The Real Frank Zappa Book, "for our beloved friends in the British Isles ... it stands out as the only 'good' Zappa album ever released" (p. 109). It doesn't have any of the interruptions, surprises, snorks, obscenities or outbreaks of chaos or spoken-word which mark his other releases. Even the Rolling Stone writer Lester Bangs - never a fan of the avantgarde - liked it! Hot Rats occupies the same position in Britain as Fillmore East does in Australia, Apostrophe(') in the United States and Joe's Garage in Norway - Zappa's "popular" album, the one which non-Zappa fans will tolerate. With Zappa, commercial success stems from accident rather than design. As he put it, his music is not designed as product. It does not reinforce anyone's lifestyle or "orientation towards the future": if it is successful, it is an accident.

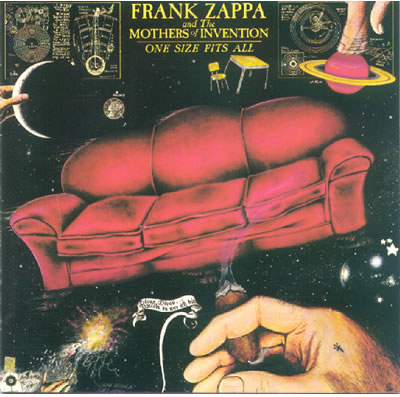

But why, of all Zappa's records, should One Size Fits All top the T'Mershi Duween poll in both 1989 and 1991? I believe every one of Frank Zappa's albums is "fractal" - like a crystal or the cell with its DNA, every part contains enough information to reconstruct the whole. You investigate any song or tune or lyric, and find Zappa's whole universe inside it - the amoral libidinal energy, the scepticism about cultural and social hierarchy, the impatience with respect and decorum, the joy in the absurd and in making opposites collide. Yet there is something special about One Size Fits All, and it is not by chance that a poll of hardcore fans - subscribers to a Zappa fanzine - should choose it as their "favourite album". One Size Fits All weaves together all his themes into a multi-coloured knot which is both live and studio, spontaneous and composed, collective and individual, cosmic and blasphemous, serious and funny. It finds the infinite in the finite - which is you, listening to a record.

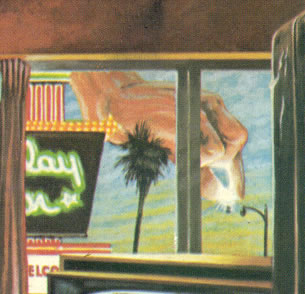

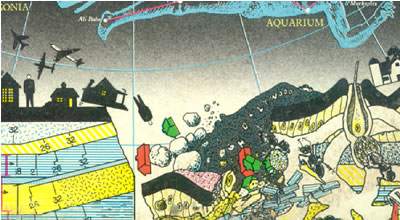

Daniel Rohr and Theater "Neumarkt" from Zürich performed Alles über Zappa here at the Kamptheater in Bad Doberan last year. They put a large maroon sofa centre-stage. This was inspired by the cover of One Size Fits All. Cal Schenkel incorporated a sofa drawn by Lynn Lascaro into his design. Schenkel also included a coin, Letraset houses, Letraset people and aeroplanes, and the London Underground (or "tube") map showing the correct station for reaching the Royal Festival Hall, but linked to stations in New York and Los Angeles. These are the dreamthoughts of a travelling musicians, experiencing the world's metropolises as one huge city: Schenkel found a graphic equivalent by creating a mad, all-inclusive subway map.

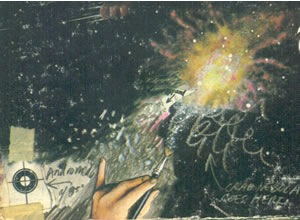

Cal Schenkel made appropriate covers for Zappa's records because he has a similar Dadaist sensibility. Instead of portraying a subject from life like "proper artist", he collages together elements he finds lying around. In the bottom left-hand corner, he makes this "collage method" explicit. He uses a "found" diagram to illustrate the constellation Andromeda - it's stuck onto the picture with masking tape. Like Zappa's music - what he called his Project/Object - the artist proceeds by incoporating foreign elements, just as biological organisms themselves do (i. e. by eating and digesting).

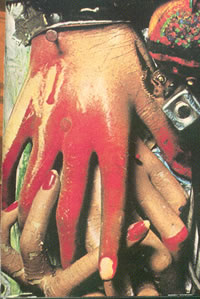

Another feature of Zappa covers is they are always full of hands. This motif began with the hand of the clothes dummy sticking up into the Sgnt. Pepper parody of We're Only In It For The Money.

In Uncle Meat, Weasels Ripped My Flesh, Burnt Weeny Sandwich and Overnite Sensation (not to mention Joe's Garage Acts II & III), hands come in from the outside.

[

In all ways, One Size Fits All is a "super" Zappa album, with everything quadrupled, everything in "quad". So on the One Size Fits All cover there are no less than four hands coming in from outside:

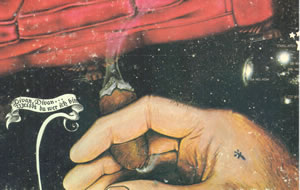

Note the cross tattooed on the hand holding the cigar - a cross with three lines radiating from it. This was called a "Pachuco cross", and I'll be coming back to it later.

These hands tell us that what we are seeing and hearing is not "music by magic by people that happen/To enter the world of a strange purple Jello" - to quote "Absolutely Free" from We're Only In It For The Money - but motifs placed inside a frame on purpose. As Zappa said in The Real Frank Zappa Book, a frame allows you to distinguish your art from "some shit on the wall". Like the Dadaists, Zappa insists that art is not a magical window on a higher, mysterious realm, not a transcendental experience, but a collection of everyday things assembled for your attention.

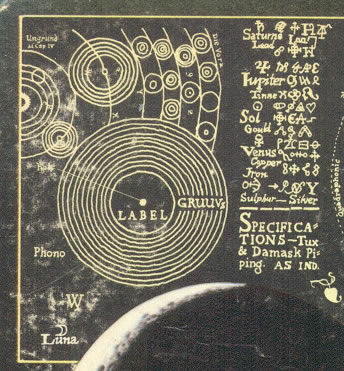

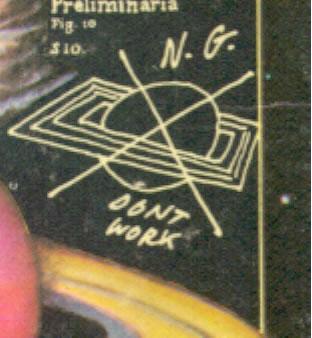

For the cover of One Size Fits All, Schenkel drew diagrams in the style of 17th-century engravings, referencing the epoch before art and science were split apart into separate disciplines. However, what one of his diagrams describes is an up-to-date product of modern technology - the 12" vinyl record:

the "Phono" with its grooves ("GRUUVs"), label ("LABEL") and hole ("hole"). The alchemical symbols for the various elements are also listed.

This kind of "cosmic archaism" was not restricted to Zappa and Schenkel. In the same year, 1975, Tamla Motown released Cosmic Truth by The Undisputed Truth, Norman Whitfield's funk troupe. Like One Size Fits All, the album includes a song about UFOs. The cover likewise referenced the stars - comparing them to the "stars" playing the music - and the world-pictures and zodiacs of the first printed books

Cosmic Truth included the famous woodcut where a pilgrim pushes his head beyond the canopy of the stars and sees the glories beyond ("canopy of the stars" is an interesting phrase - the German word for sofa is "Kanapee").

In 1975, The New Birth issued an album named Blind Baby on the Buddha label. The musicians were shown against a starry sky, with their star sign, instrument and birthplace listed.

In the same year, George Duke recorded an album with a DJ reading out horoscopes for the different star signs (unfortunately, I disliked this one so much that I sold it straight away, so I can't show it to you). In 1975, astrology was hip among black audiences, so One Size Fits All picked up on that, just as Zappa encouraged George Duke and Napoleon Murphy Brock to improvise contemporary street "jive" on stage.

As usual, Zappa's attitude is both celebratory and satirical. In "Camarillo Brillo" on Overnite Sensation, the voodoo accessories of the magic mama are revealed as phony commodities compared to the "unconcho" - unconscious - experienced during the sex act. With "Camarillo Brillo", Zappa constructed a song which conveys Wilhelm Reich's observation that:Mysticism is nothing other than unconscious longing for orgasm (cosmic plasmatic sensations). (The Mass Psychology of Fascism, 1946, Penguin translation, p. 199)

In "Dancin' Fool" on Sheik Yerbouti and "Sy Borg" on Joe's Garage, star signs have become even more degraded: they are now simply an excuse for the robotic exclamations of men looking for a fuck (or what Zappa calls "American love poetry").

Unlike the Motown and Buddha cover designers, Schenkel does not simply exploit antique imagery for its "cosmic" vibe, thus distracting attention from the banality of the commercial product. He goes in the opposite direction. He satirises mystical concepts by introducing everyday household objects - very much in the same spirit as the games Zappa and Beefheart used to play with vacuum cleaners.

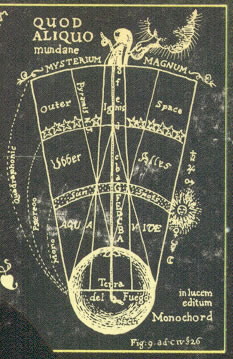

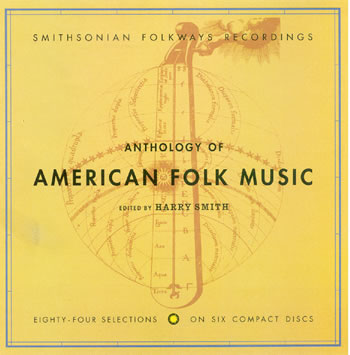

This illustrates the various stages of hi-fi technology: mono, stereo, quodrophonic. Overnite Sensation was issued in quad, but the format never caught on - people found that they had only two ears, so that having four-way stereos wasn't necessary. In the corner of the cover, the initials CS and LL - for Cal Schenkel and Lynn Lascaro - are written over the date 1675. Schenkel is trying to make us look at the record industry from the point of view of the historian - all its claims to fidelity and truth and relevance will one day look as quaint as the diagrams in 17th-century books. The diagram distiguishes various levels: the earth, renamed "Terra del Fuego", the atmosphere "Ubber Alles" (a reference to the song "Deutschland Uber Alles", which also echoed in Daniel Rohr's title Alles über Zappa), and then "Outer Space", leading up to the "Mysterium Magnum". It is based on an etching by Theodore de Bry in a compendium of arcane knowledge put together by Robert Fludd, a 17th-century Englishman responsible for some of the most elaborately-illustrated printed books of his day. De Bry's diagram showed God's hand tuning the "celestial monochord" - another hand coming in from beyond the frame - and draws parallels between the harmonic series first codified by Pythagorus and the four elements - earth, water, air and fire. This diagram had been used for the covers of the three volumes of Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music, issued in 1952 on Folkways Records, a collection of American music from Smith's collection of 78rpm discs - blues, gospel, hokum, hillbilly - which gave the burgeoning folk song movement its repertoire. They came in the colours red, blue and green, symbolising fire, air and water (the fourth compilation, which would have been brown for earth, was only issued after Smith's death).

Like Zappa's music, Schenkel's use of Fludd's diagram is playful rather than reverent. It laughs at hippie mysticism. Laughter, like sexual attraction, is an involuntary reaction - a message from the "unconcho" rather than the conscious mind. Like music, laughter and sex show up consciousness as repressed and restrictive.

Schenkel illustrates Mercury using an American coin (a nickel and a dime are referenced in "Can't Afford No Shoes"). The coin shows the head of the Roman god - identifiable via his winged helmet - plus the inscriptions "Liberty" and "In God We Trust". If we are to trust God, it is legitimate to ask where he is and what he's doing here ...

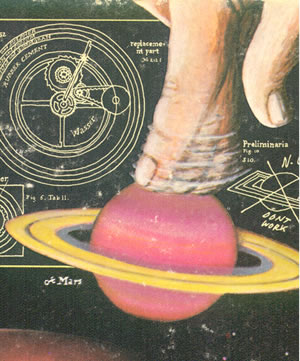

The "hand of God" emerging from a cloud is a graphical cliche of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Theodore de Bry's engraving, it signifies that the beauty and order of the harmonic series was shaped by a conscious entity who made Man in His own image. Schenkel takes this humanoid idea of God to ridiculous extremes. If God created harmony, he must have put the spin on Saturn with his fingers. Maybe, like a human being, he also made mistakes, like designing Saturn with a square ring.

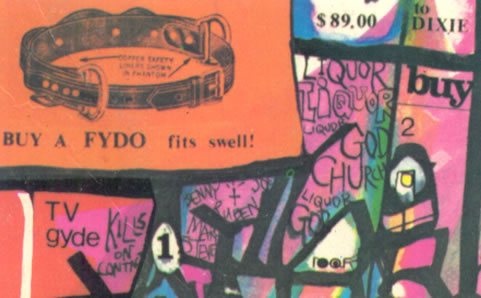

In the Poodle Lectures of 1977, Zappa had God making three big mistakes - man, woo-man and the poodle. If God is human, He must indulge in typical pleasures. Schenkel's planetary diagram has a "Chewy carmel center" like a sweet, and the various layers of the diagram "showing method of spin in Saturn" are labelled "Sodium und Sulpher", "Scotch und Sodium" and "Sodium und Gomorrah", conflating primal cosmic elements, old-fashioned ways of consuming whiskey and divine retribution. And like the archetypal boss, God smokes a cigar: Schenkel placed a cigar-holding hand just where your own right hand would appear if you were holding the album cover. The tattoo on this hand was refered to by Zappa and the Mothers of Invention as a "Pachuco cross" - the kind of symbol a Mexican American, i. e a Roman Catholic, might have tattooed on his hand. It portrays the cross, and the three lines signify the Holy Trinity - Father, Son and Holy Ghost. A Pachuco cross also appears on the back of of Absolutely Free, the one cover drawn by Zappa himself.

Here the Pachuco cross is associated with all kinds of social ills, including TV - "kills on contact" - liquor stores, churches and God. The names "Benny", "Ruben", "Martha", "Steve" and "Joe" appear round the cross - looking like graffiti by a teenage gang. In Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, the band appear with dog snouts, later explained as the result of an evil plot by Uncle Meat (just like the potato heads produced by the Evil Prince's "secret POTIUM" in Thing-Fish). "The story of Ruben and the Jets" on that album concludes: "Ruben has three dogs, Benny, Baby and Martha". It is as if Ruben's gang is imaginary, he's simply written up the names of his dogs! The hoarding which says "Buy a FYDO fits swell" initiates poodle continuity in Zappa's oeuvre (and also anticipates the title of One Size Fits All). All these details are part of the chaos of a typical American high street, dominated by cars, advertisments, chimneys, the American flag, the Draft Board and dead trees: as usual, rather than deliver a message Zappa documents everyday trivia. However, like Philip K. Dick, whose first published story ["Roog", Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1953] was told from the point of view of a dog, and Franz Kafka [whose "Investigations of a Dog" is about a dog's relationship to music], Zappa uses comparison with dogs to try and establish what humans are and what they might be. Perhaps the Pachuco cross on God's hand is an indication that God might be best interpreted backwards - as a doG.

Perhaps the listener is both God and a dog, torn between aspirations to the divine and his or her biological urges.

The "Sofa" song was part of a blasphemous and obscene suite of songs which Zappa first performed with Flo and Eddie on his European tour in 1971 (for example, at The Ahoy, Rotterdam, 27-Nov-1971). God makes a sex movie by making his girlfriend fuck a magic pig named Squat on their sofa. It includes songs later released as "Once Upon A Time" [Stage Vol. 1], "Sofa" [OSFA] and "Stick It Out" [Joe's Garage Acts II & III], thus seguing two songs with German lyrics which were released four years apart. At this time "Sofa" was introduced by a few bars of German waltz music in an arrangement that smelled heavily of Bierkellern. It includes the words "Ich bin The Chrome Dinette", an example of which duly appears floating behind the sofa on Schenkel's cover.

For English-speaking listeners, a fulsome tune like "Sofa" sung in German - however beer-soaked the music - immediately evokes the gigantesque operas of Richard Wagner. In Rotterdam, Zappa and Flo and Eddie apologised for singing in German, and explain that it's because it's sung by "God". As with the reference to "Uber Alles" on the cover, Zappa is mocking the pompous nineteenth-century trappings of Hitler and the Nazis.

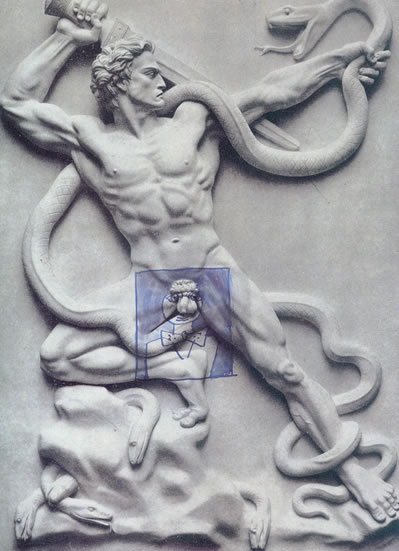

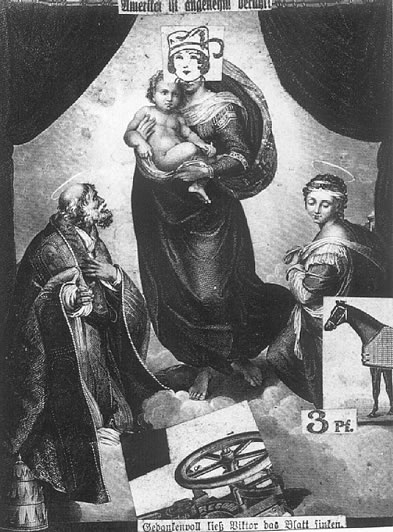

The Beatles goose-stepped in their hotel in Hamburg in their early days to make a "joke"; the Rolling Stones dressed in Gestapo uniforms on an album sleeve in order to appear "decadent"; and Mark E. Smith of the Fall siegheiled a Tübingen audience in 1983. So was Frank Zappa simply being "anti-German" and sadistically reviving painful memories of Nazism and the Second World War, the kind of cheap shots used by these other rock acts? Zappa was more sensitive to history than that. This sensitivity explains why his music became popular amongst radical spirits in both "western Germany" and "eastern Europe", even when the countries were supposedly divided by opposed ideologies. Zappa's mockery of German culture was not that of an outsider, an "American", it came out of sympathy with the progressive, modernist culture which the Nazis suppressed - that of Weimar, of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill and the Dadaists. Zappa's "Sofa" song, degrading religious and political mystique using the low weapons of comedy and sex, was just like Dadaist Willi Baumeister, who in 1941 defaced a postcard of a marble relief-statue by Arno Breker ("The Avenger", the same theme of vengeance - Vergeltung - which supplied the initial "V" for the V1 and V2 rockets, prototypes for the USA's cruise missiles), Hitler's favourite sculptor.

Zappa said about Dada:

In the early days, I didn't even know what to call the stuff my life was made of. You can imagine my delight when I discovered that someone in a distant land had the same idea - AND a nice, short name for it.

However, unlike the New York art scene which embraced Marcel Duchamp's urinal and bottle-rack - his "readymades" - Zappa's Dada was not conceptual or anti-art or paradoxical. It wasn't "art" at all, it was pop music - populist and accessible, critical and political. It was mass-produced, it wasn't for rich people to invest in, it could reach people all over the globe, but still without affirming the values of Coca-Cola and McDonald's.

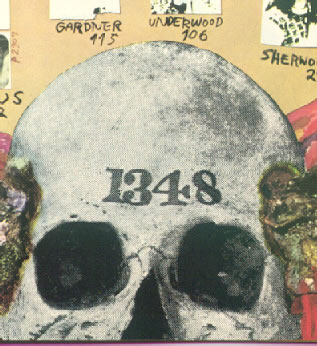

The back cover of One Size Fits All shows a zodiac, but Schenkel has replaced every constellation and star name with references to references and jokes current with Frank and the Mothers. When Schenkel is consulted about his artwork, he is surprised by the amount of significance which fans and Zappologists read into it. For example, he insists that the number "1348" which appears on the skull on the back of Uncle Meat

was simply random, one of many numbered skulls he could have chosen. Yet 1348 happens to be the year of the Bubonic Plague - the Black Death - in Europe, and Zappa subtitled the tune "Dog Breath" on the album with the phrase "In The Year of the Plague"! Around the edge of the zodiac appear words which were originally spoken by Flo and Eddie on 7 August 1971 at Pauley Pavilion in Los Angeles, a recording of which was issued on the album Just Another band From L.A.. I should like to thank Richard Hemmings - otherwise known as "Evil Dick" - for pointing out that these words were improvised by Flo and Eddie. Zappa knew that allowing unscripted moments into his artwork would generate much greater resonances than complete control.

Their sequence of random associations cited on the back cover of One Size Fits All finishes "funny cars ... city of industry". In his book The Conquest of Cool (Chicago, 1997), Thomas Frank writes about the advertising industry's use of flower power motifs. He traces back the use of non-conformist, "hip" ideas in 60s advertising to the Volkswagen campaign carried out by the Doyle Dean Bernbach agency in 1959. "Could it be, " asked one of the Volkswagen ads, "that ours aren't the funny-looking cars after all?" (p. 63). Greggery Peccary, the ultra-hip advertsing executive, drove a Volkswagen. In the late 60s, the Scali, McCabe and Sloves agency issued ads for Volvo in a similar, but still more pointed style. In 1968, they printed publicity photos of Plymouth, Chevrolet and Ford Fairlan cars from 1957 - all products of the giant manufacturers based in Detroit - and asked underneath: "The exciting new cars of 11 years ago. Where, oh where, are they now?". In contrast, continued the ad, Volvos "don't change much," they aren't "new and exciting for 1968. So [they] won't be old and funny-looking for 1969." (p. 146) The phrase "Funny cars ... City of Industry" points at the way commodity promotion and planned obsolescence manipulate our notions of taste: like the whole of One Size Fits All, it asks what can be authentic in an era of commodity production.

To Flo & Eddie's string of free associations, Schenkel added the final words of Lump Gravy: "round things are ... boring". This implies total rejection of star signs and zodiacs and their projection of cosmic circularity - fate - on human existence. Evil Dick is currently completing a doctorate on "randomness" at Leicester University. He points out that Zappa was fascinated by tape recording at a very early stage, but rarely if ever used tape loops (unlike, say, Brian Eno). Zappa disliked repetition in music (it was his main criticism of Harry Partch), prefering musical events that were singular. Where he uses repetition it is rarely mechanical in the manner of tape loops or repeated samples, and is more about the tension of forcing musicians to repeat themselves: the point is the moment where the pattern is broken. This agrees philosophically with Hegel, whose dialectic refused to place unfolding historical events under unchanging abstract categories. It is the specificity of Flo & Eddie's free-associated gibberish which fascinated Zappa.

Zappa loved Dada, and his art is motivated by similar principles - a love of play, chance and suggestion rather than assertion and correctness. However, the Dadaists were no random moment in European culture. The possibilities they envisaged were extinguished by Nazism and world war, but their assault on moribund cultural forms was anticipated in classical German philosophy. The artistic strategies of Dada may appear wilful and irrational, but they carry the profoundest philosophical thoughts about democracy. The culture which the Nazis hijacked - pretending that their ranks of stupid, conformist, anti-semitic professors were the heirs of Plato, Goethe, Beethoven, Hegel - was originally one of criticism and freedom. Dada, like Zappa, was revolutionary classicism: the tradition which, to fulfill itself, needs to revolt against contemporary sterility, compromise and regression.

The reason I am calling this talk "Phenomenology of One Size Fits All: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel und Frank Zappa" is NOT because I believe Frank Zappa sat around reading Hegel. I read my own writings to him shortly before he died, and he told me he had never read any philosophy at all. He said he lost the thread everytime I quoted Theodor Adorno, the Hegelian-Marxist philosopher whose statements on music provide a multitude of "coincidental" insights into Zappa's harmonic and lyric choices. I believe the connection between Hegel and Zappa is far more basic and real than "influence": it has to do with a scientific grasp of what can be historically true and culturally progressive in an era of commodity production.

Hegel's philosophy is vast and difficult. Different interpreters seem to be speaking about a completely different philosopher. The same interpreters - for example Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels - say at one moment they're his "loyal pupils", at another time that he must be turned upside down, that his "idealism" must be replaced by thorough-going "materialism". So I am going to concentrate on a single statement Hegel made, and explain why I think Dada and Zappa carry out Hegel's philosophical programme, even if they weren't philosophers, but artists and a musician.

The statement I'm interested in occurs in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, an early work which sold widely and made Hegel's name as a radical philosopher - the Jacques Derrida of his day. It is no accident that it is a statement emphasized by Raya Dunayevskaya and the circle of Marxist revolutionaries around her in Detroit. Together with the Trinidadian revolutionary C. L. R. James, Dunayevskaya formed the Johnson-Forest Tendency in 1947. They said that Stalin's Russia was not "socialist" but "state capitalist", and called for renewed study of Hegel and dialectics. They - in common with both Dada and Zappa - rejected conventional assumptions about the place of advanced thought and culture in society. Instead of seeing the finest products of the human mind as belonging to power and privilege, Dunayeskaya and James believed that the most progressive social ideas of their time were held by black car workers in Detroit. In fact, the quote I am about to show you - on a slide, because Hegel's thoughts are complex, and they are easier read than heard - was a favourite of Charles Denby, the autoworker who edited Notes & Letters, the journal of the Dunayevskaya circle in Detroit (this journal survives today - I bought one on the big anti-war demonstration in London in February).

In her "Notes on Hegel's Phenomenology", written in December 1960, Raya Dunayevskaya explored what Hegel had to say about culture. Her advice wasif you keep in mind what Marx meant by "superstructure", you will be able to swim along with Hegel's critique of culture. (The Power of Negativity: Selected Writings on the Dialectic in Hegel and Marx, p. 40).

Dunayesvskaya quotes from paragraph §486 of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, which is about how life is process and impurity - change - rather than static self-sufficiency (a philosophical position Zappologists might recognise as "Round things are ... boring").

Nothing has a Spirit that is grounded within itself and dwells within it, but each has its being in something outside of and alien to it. The equilibrium of the whole is not the unity which remains with itself, nor the contentment that comes from having returned into itself, but rests on the alienation of opposites.

Nichts hat einen in ihm selbst gegründeten und inwohnenden Geist, sondern ist außer sich in einem fremden, das Gleichgewicht des Ganzen nicht die bei sich selbst bleibende Einheit und ihre in sich zurückgekehrte Beruhigung, sondern beruht auf der Entfremdung des Entgegengesetzten. (Ullstein edition, p. 275)

In other words, there is no self-sufficient, immortal "soul" in the Platonic or Christian sense. Human beings are living process whereby the individual works on nature (as when it consumes food), and aspires to something that is not itself, and is indeed alien to it (for example, sexual congress or death). Despite Hegel's idealism and his use of the word "Spirit", this view of the self is actually more compatible with materialism and scientific fact than notions of the "soul".

Dunayevskaya cites Hegel on the Enlightenment in 18th-century France, and the campaign against religious superstition and bigotry launched by Voltaire, Rousseau and Diderot.In its hostility to Faith as the alien realm of essence lying in the beyond, it's what we call the Enlightenment. This Enlightenment alienates Spirit in the realm of Faith, too, where Spirit tries to take refuge, and where it believes it enjoys unruffled peace. It upsets the housekeeping of Spirit in the household of Faith by bringing into that household the tools and utensils of this world, a world that the Spirit cannot deny is its own, because its consciousness likewise belongs to it.

Gegen den Glauben als das fremde jenseits liegende Reich des Wesens gekehrt, ist sie die Aufklärung. Diese vollendet auch an diesem Reiche, wohin sich der entfremdete Geist, als in das Bewußtsein der sich selbst gleichen Ruhe rettet, die Entfremdung. Sie verwirrt ihm die Haushaltung, die er hier führt, dadurch, daß sie die Gerätschaften der dieseitigen Welt hineinbringt, die er als sein Eigentum nicht verleugnen kann, weil sein Bewußtsein ihr gleichfalls angehört. (Ullstein edition, p. 276)

Hegel here predicts how Marx and Engels would desecrate idealist philosophy (which they attacked as a new religion, the "German Ideology"). They brought into philosophy the issues of capital, labour and rent, very much the "tools and utensils of this world" ("die Gerätschaften der dieseitigen Welt"). But Hegel also anticipated the Dadaists, who created a peculiarly hilarious giddiness by pasting manufacturers' catalogue-images of household objects onto the transcendental horizons of religion, nature and power. Look at Mz 151. Wenzel Kind (Knave Child) (1921) by Kurt Schwitters; Two Young Girls Promenade across the Sky (1920) by Max Ernst and This was before HRH the late Duke of Clarence and Avondale. Now it is a Merzpicture. Sorry! (1947) by Schwitters.

Hegel also anticipated how Zappa would bring "household tools and utensils" into the new refuges of "Faith": astrology and belief in flying saucers.

The first song on One Size Fits All, "Inca Roads", uses motifs from Erich Von Däniken's Erinnerungen an die Zukunft (Econ-Verlag, 1968), which in English translation became a bestseller of the early-70s: Chariots of the Gods? Unsolved Mysteries of the Past. The question asked on the cover of the 1972 Corgi edition was: "Was God an astronaut?". Von Däniken believed that earthworks by the Incas proved that the "Gods" worshipped by primitive peoples were actually visitors from outer space.

Not far from the sea, in the Peruvian spurs of the Andes, lies the ancient city of Nazca. The Palpa valley contains a strip of level ground some 37 miles long and one mile wide that iss cattered with bits of stone resembling pieces of rusty iron. The inhabitants call this region pampa, although any vegetation is out of the question there. If you fly over this teritory - the plain of Nazca - you can make out gigantic lines, laid out geometrically, some of which run parallel to each other, while others intersect or are surrounded by large trapezoidal areas.

The archeaologists say they are Inca roads.

A preposterous idea! What use were roads that run parallel to each other to the Incas? That intersect? That are laid out in a plain and come to a sudden end?

[Erich Von Däniken, Chariots of the Gods?, London: Corgi, 1972, p. 31]Seen from the air, the clear-cut impression that the 37-mile-long plain of Nazca made on me was that of an airfield!

What is so far-fetched about the idea? [same, p. 32]Responding with paranoid intensity to random historical artefacts, he printed a Mayan manuscript showing a man lying back on a couch in a house with a steeple and claimed it was an astronaut inside a rocket ('Those strange markings at the foot of the drawing can only be an indication of the flames and gases coming from the propulsion unit'). Excerpts from his books were printed in popular newspapers and magazines throughout the world.

As usual with Zappa, it is not a simple matter to determine his own "opinion". George Duke sings the lead vocal on "Inca Roads". In 1974 and 1975, George Duke released Feel and The Aura Will Prevail on the German MPS label. Zappa played on two tracks on the first record (under the name "Obdewl'l X"), and Duke covered Zappa's tunes "Echidna's Arf" and "Uncle Remus" on the second. Both albums feature Airto Moreira, the Brazilian percussionist and member of Return To Forever, Chick Corea's fusion group. Corea left the jazz avantgarde when he converted to L. Ron Hubbard's Scientology cult - some people claimed he was instructed by Hubbard to make money with his music - and Return To Forever adopted Hubbard's mixture of mysticism and Science Fiction. So although Zappa was satirising Von Däniken and the Sci-Fi fantasies of fashionable Soul and Fusion bands, he was using the voice of someone involved with that scene (Zappa admired the musicianship of the Mahavishnu Orchestra, yet "Cosmik Debris" (1972) was nevertheless an attack on Guru Sri Chinmoy, whom McLaughlin and Santana pledged allegiance to on Love Devotion Surrender (1973)).

Actually, "Inca Roads" is a model example of Zappa's satire. He does not explicitly criticise or polemicise. Indeed, he appears to revel in the possibilities of Von Däniken's theory. There is even some poignancy in the questionDid the Indians, first on the bill

Carve up the hillas the listener is asked to imagine the spiritual strivings of a vanquished civilisation. However, everything goes weird when the alien vehicle becomes a "booger bear" - apparently female - reference is made to the Armadillo venue in Austin, Texas (where the next album, Bongo Fury, was recorded) and to the musicians Ruth Underwood and Chester Thompson. Von Däniken's theory transforms into a series of infantile band in-jokes (people complain that Zappa's lyrics are "obscure" - touring band in-jokes are always obscure, often to members of the band themselves, it's just that few bands bother to make songs out of them). Zappa's objection to mysticism is not that it lacks scientific accuracy and empirical evidence, but that it produces awe and reverence, repressing humour and personality.

"Can't Afford No Shoes" is a protest song about the state of the economy. It contains another jibe against mystical solutions to material problems:Chump Hare Rama, ain't no good to try

"Sofa" is a special song in Zappa's oeuvre. It appears on One Size Fits All twice - as an instrumental, and with a vocal overdub. He re-released it two years later in another arrangement on Zappa in New York, where he called it "an arousing waltz" and mentioned that the album it was on was "not very popular". It is the first tune on You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore Vol. 1, and another version concludes that 2CD set as well. Why did he choose to introduce this particular "household utensil" into the cosmic fantasies of Scientologists and UFO-spotters?

Like the motifs in a dream, a symbol like Zappa's sofa is over-determined. It works artistically because it condenses many meanings. Bizarre "coincidences" surround it, making it a fine example of what Gail Zappa called Frank's "prescience". It has a musical resonance: "tonic sol-fa" is the name for a musical system. It was introduced into England by J. S. Curwen in the 1840s. "Sol-fa" names the notes of the major scale: "doh, ray, me, fah, soh, lah, te - doh". So the sofa could be "sol-fa", a musical system.

The word sofa also connects to God. In kabbalistic interpretions of Hebrew scripture, the term 'en-sof is keenly contested. Rabbi Ben Zio Bokser, for example, begins his The World of the Caballah, a guide to the thought of the sixteenth-century Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague, with En Sof:God is ... En Sof, the Infinite, the Boundless One.

(p. 4)Gershom Scholem points out that in Hebrew scripture 'en-sof was originally an adverbial phrase meaning "up to infinity" (Origins of the Kabbalah, p. 130), but that it became a name for God through "mystical interpretation" (p. 266). The 'en-sof problem was hotly debated by Jewish and Christian scholars and mystics throughout the medieval period. Scholem says:

That which, from one perspective, is called 'en-sof is, from another perspective, the Nought or the primordial will. (p. 443)

In his philosophical dialogues, Plato had Socrates talk about the "ideal form of the couch": an Ancient Greek sofa. In British analytical philosophy, a frequently used figure for an object is the chair or table. Abstract thought starts from its immediate surroundings, and there is nothing so basic - or materially necessary - for a reading person as what we are sitting upon. This gets forgotten when philosophical thought forgets the imaginer behind the imagination and becomes sublime, pompous and reverential - all the sapects of religion which Zappa hated. But why the sofa, rather than the couch or chair and table (which of course do appear on the cover, as the Chrome Dinette)?

Thea reason for the centrality of the sofa in Zappa's oeuvre is that, like the piano among instruments, the sofa is the bourgeois item of furniture par excellence. In 1785, the English poet William Cowper published a long poem called The Task. Its first book was called "The Sofa", and began:I sing the Sofa. I who lately sang

Truth, Hope, and Charity, and touch'd with awe

The solemn chords, and with a trembling hand,

Escaped with pain from that adventurous flight,

Now seek repose upon an humbler theme ...An "advertisment" at the beginning of The Task explained that the subject of the "sofa" had been assigned to the poet by a certain lady, thus becoming "a task" he could not refuse. In parodying the opening of an epic by Homer or Virgil, Cowper sought the opposite of the heroic, and found it in bourgeois domestic comfort - as usual presided over by a desirable female.

In One Size Fits All, Zappa registers a similar bathos - the descent from the sublime to the ridiculous, from the divine to the domestic - in the song "Evelyn, a Modified Dog", which describes a dog responding to harmonic reverberation. The atmosphere of the song derives from the lengthy titles (so long they are almost poems) given to his paintings by artist Donald Roller Wilson, who supplied the Arf Society with their doggie logo (a Pomeranian, a logical choice for a society based in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern): something sinister - sexual, overripe and nightmarish - lurks in the clutter of the bourgeois domestic interior. Theodor Adorno, ever alert to the iconography of class, castigatedthe philistine cliché of the body that stretches out on a sofa while the soul soars to rarefied heights (Aesthetic Theory, pp. 144-5)

das spießbürgerliche Convenu vom Leib, der auf dem Kanapee bleibt, während die Seele sich in die Höh' schwingt (Ästhetische Theorie, Suhrkamp, p. 151)

By putting a sofa on the cover of his album, Zappa mocks the cosmic afflatus of Scientology and Fusion. The sofa reminds the listener where he or she actually is: sitting at home, listening to a record. However, this deflation of cosmic pretension is not simply cruel and mean-spirited. A person sitting on a sofa and listening to a record - perhaps smoking a cigar, or asking the sofa "Divan, Divan ... Weisst du wer ich bin" - is a consciousness perceiving the universe and is hence in a sense godlike.

The song which concludes side one of One Size Fits All - at least in the vinyl version it was originally programmed for - is "Po-Jama People". In an interview, Zappa reminisced about the old-fashioned pyjamas he and his family used to wear - thelittle trap-door back aroun' 'em

describes an opening in the seat of the one-piece pyjamas which allowed wearers to use the toilet. In another interview, Zappa explained that "Po-Jama People" was about the musicians in The Grand Wazoo band - session players who played chess in their spare time and didn't engage in the extrovert behaviour of musicians like Napoleon Murphy Brock, Ruth Underwood and Chester Thompson.

The opening lines rewrite the nursery rhymePease-pudding hot, pease-pudding cold

Pease-pudding in the pot nine-days-oldwhile the music - basically an extravagant guitar solo with all the other musicians, especially George Duke, crashing along behind - is raucous, out of tune, out of time and flailing. Appropriately it is the musical opposite of the tidy chamber jazz of The Grand Wazoo, which Zappa described as "cranial pseudo-jazette" [FZ NME 17 April 1976]. It is also the opposite of the tight neo-classicism of fusion groups like Return To Forever. Liking this kind of music helps explain why Zappa produced Grand Funk Railroad the next year: Good Singin' Good Playin' (EMI), a decision which bewildered many critics. For them, George Duke and Mark Farner occupied different universes: they thought Zappa was schizophrenic. Actually, Zappa's music and social attitude are all of a piece: what he hated most was the suppression of personality beneath abstract schemas, which is why his albums emphasize the contingent, the accidental and the idiosyncratic.

In an interview Zappa described "Florentine Pogen" as a love song (Nigey Lennon claims it's about her, though there isn't much internal evidence to confirm this). Harmonically, it's a derivative of "Penguin In Bondage", a mode which was to surface later in "Jewish Princess" and "Fine Girl". However, unlike those two songs, the tone is not provocative or cynical. As with the lyrics of Uncle Meat, the words seem to have been "scientifically prepared from a random series of syllables, dreams, neuroses & private jokes that nobody except the members of the band ever laugh at". Sigmund Freud wrote books on dreams, neuroses and jokes. Zappa's songs may resist conventional interpretation, but they certainly invite psychoanalysis. If it's a love song, then "Florentine Pogen" is unique in its quantity of indelicate, mechanical and downright unromantic vocabulary. Who else could write a love song with "fan belts", "batteries" and "crab cakes"? Like "Inca Roads", any ostensible subject matter disappears into references to onstage buffoonery and roadmanager Marty Perellis's gorilla suit. Zappa's songs refuse interpretation which isn't musical: the point is the splendid, purple power of the arrangement, its ritualistic, intoxicating gorgeousness, and the musicians whose efforts made it possible. Once his musicians had learned his songs, Zappa said the written notes went into "muscle memory". One reason that Zappa's records are so good compared to those contemporary classical composers and contrived pop bands is that he only recorded once musicians were playing from "muscle memory" - he got intuitive rather than conscious performances.

Though he was a professional philosopher who dealt in abstractions, Hegel was aware of this kind of knowledge.The facility we attain in any sort of knowledge, art, or technical expertise, consists in having the particular knowledge or kind of action present to our mind in any case that occurs, even, we may say, immediate in our limbs, in an outgoing activity. (Logic §66)

However, Zappa was not simply nihilist about meaning. Note that Zappa talked about the scientific preparation of a "random series of syllables, dreams, neuroses & private jokes". Like a 12-tone composer subjecting a random tone-row to Schoenberg's inversions and retrogrades, or Dadaist Kurt Scwitters gluing a camenbert wrapper to a canvas, Zappa pays attention to the rubbish he has collated. For example, the final

Hratche-plche

Hratche-plcheof "Florentine Pogen" is a transcription of a mouth noise - but its appearance at the conclusion to the song is no more accidental than anything else in Zappa's oeuvre. In the original transcription of the words of "Brown Shoes Don't Make It" - printed in International Times for August 13-September 13 1967 after MGM refused to include a lyric sheet in the album - the lines

But back in the bed his teenage queen

Is rocking and rolling and acting obscene

Baby! Baby! Baby! Baby!are followed by the lines

Hratche-plche, Hratche-plce

Hratche-plche, Hratche-plceThese were omitted in the version which appeared in Carl Weissner's Plastic People Songbuch published by Zweitausendeins in 1977, and also in the foldout accompanying CD reissue. In fact, I suffered a bout of paranoia in trying to locate them - I had notes I made in 1974, but couldn't find the copy of International Times. Like anyone in a Zappa pickle, I telephoned my Zappa guru. My Zappa guru is called Gamma. He wasn't there (he was out walking his poodle Jakes). I left an answerphone message. This was his answerphone reply.

[You've got to hear this to get the point. Mick Zeunig, Arf Society soundman and producer, copied my mini-disc for inclusion on the Zappanale #14 CD ... check it out! Gamma spelt out "hratche-plche" from his copy of International Times and found "hot rats" in the first four letters ...]

Why am I bothering about these micro-details of Zappology and taping Gamma reciting "hratche-plche" on my answerphone - and then broadcasting it to you? Because they show that every motif - down to the last letter - had for Zappa a poetic charge that demanded respect. That is why his oeuvre rewards the obsessional attention to detail lavished on it by Zappaphiles. "Hratche-plche" was a private symbol for the transcription of a lustful mouth-noise, one he used for both the drooling city-hall bureaucrats and for the conclusion of a "love song" liek "Florentine Pogen". For Zappa, sexual desire is objective, untainted by moral distinctions between "bad" lust and "good" love - which really translate to other people's desire ("bad") and my own ("good", unless it upsets property relations, in which case it is "bad"). Zappa hates all this talk of "good" and "bad": the only problem for Zappa is the blocking or repression of eros, wherever it is found. Again, this amoral attitude is like that of psychoanalysis, which treats sexual urges as facts rather than sin. It also relates to Hegel, who denounced the double-thinking of conventional piety. As Hegel points out in Phenomenology of Spirit:the consciousness of virtue rests on this distinction between the in-itself and being, a distinction which has no truth §389

Das Bewußtsein der Tugend aber reuht auf diesem Unterschiede des Ansich und des Seins, der keine Wahrheit hat. (Ullstein edition, p. 222)

Hegel will have none of the useless, pious wishes of conventional morality - he wants to bring actuality and thought into congruence. Without knowing it, Zappa was a Hegelian.

"San Ber'dino" introduces us to Potato-head Bobby, later to feature in "Advance Romance" and Thing-Fish. He is a symbol of the non-intellectual, lower-class individual, source of everything Zappa likes about the blues and rock - its physical directness and its lack of hypocrisy, even its ugliness (as opposed to the standardisation implied by "beauty"). The riff Zappa uses is a classic driving riff - completely suited to the subject matter, which is a trailer-trash couple whose life revolves around driving their car on the freeway. Using Johnny "Guitar" Watson for what Zappa calls the "flambé" vocals was a stroke of genius. Johnny "Guitar" Watson's first single for King Records - under the name Young John Watson - was "Motorhead Baby", an automobile anthem he wrote with Mario Delagarde, the Puerto Rican bass player from the Johnny Otis Orchestra who held seminars on Marxism-Leninism and dialectics on the band bus and died fighting Batista in Cuba in the mid-50s. Johnny "Guitar" Watson's saxophone-like, urgent voice expresses the sheer excitement of freeway California as a land of opportunity for the deprived.

It is impossible to talk about the words of "Andy" apart from its music, the nearest thing to Edgard Varèse which Zappa ever composed - but achieved without an orchestra, instead using rock instruments and rock-studio multi-track recording. Andy de Vine was an actor in b-movie Westerns, and the whole song works as an interrogation of superficiality: how we tell from what someone says what they really are [Ansich from Seins]? Zappa expertly uses the contrast between the voices of George Duke and Johnny "Guitar" Watson. Duke's is intimate, breathy and humorous, his mouth close to the microphone so you can hear his lip smacks and wheezes. It implies depth and human warmth. Johnny "Guitar" Watson's is sleek and slick and hard, so loud and projected that the microphone must have been a foot away. The two voices alternate, an equivalent to the quandary of the song: can we believe what things are by looking at the surface? Is the interior true, or the exterior? Or is everything outside a fake, a landscape of Hollywood flats, like the scenarios experienced by Philip K. Dick's characters? Ansich oder Seins?

Hegel said:The evanescent itself must be regarded as essential ... (Phenomenology of Spirit §47)

Das Verschwindende ist vielmehr selbst als wesentlich zu betrachten ... (Ullstein edition, p. 36)

Anyone who does not believe in the immortality of the soul must take Hegel seriously on this - after all, as mortal beings we are "evanescent" but we are nevertheless "essential", however illogical this may sound to traditional (ie Platonic) philosophy.

Talking of beauty, Hegel saidWe find as characteristic constituents of the beautiful an inward something, a content, and an external rind which possesses that content as its significance. (Philosophy of Fine Art §32)

Zappa applies this dialectical logic: we don't "break through" the irrelevant details of his musical construction to find some "deep meaning" - one that in conventional music is achieved by triggering an overriding emotional response in the listener which blots out musical detail - but trace significance by paying attention to the musical surface: the everyday things assembled for your attention.

Zappa said that his music applied the principles of Alexander Calder's mobiles:In my compositions, I employ a system of weights, balances, measured tensions and releases - in some ways similar to Varèse's aesthetic. The similarities are best illustrated by comparison to a Calder mobile: a multicolored watchamacallit, dangling in space, that has big blobs of metal connected to pieces of wire, balanced ingeniously against little metal dingleberries on the other end ... So in my case, I say: "A large mass of any material will 'balance' a smaller, denser mass of any material, according to the length of the gizmo it's dangling on, and the 'balance point' to facilitate the danglement." (The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 162-163)

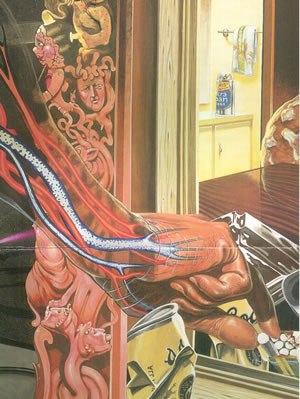

In the instrumental mid-section of "Andy", drums, bass, organ and guitar and percussion are introduced one at a time, as if to measure the tension the sounds exert on each other. The track should be listened to in conjunction with Cal Schenkel's diagram of the Sam Andreas faultline on the back cover.

Schenkel puns together ideas of the person beneath the skin and of the earth beneath its crust. Ants are portrayed as in an American child's ant farm. The San Andreas fault has opened up, bringing down Hollywood, and swallowing Monopoly houses and hotels.

There is one moment in "Andy" which is equivalent to this faultline: a brief passage of rattling percussion - woodblocks and coconut shells. It introduces Johnny "Guitar" Watson's closing vocal. This momentarily relieves the metric tension which girds the rest of the song like a twanging suspension bridge. This moment is like the "commas" of Pythagorus and Didymus, which cheat just intonation in order to produce a dynamic and logical relationship between notes: an error which allows everything to happen.

One of the characteristics of Hegel's dialectic - one emphasized by Lenin - was that "everything connects to everything else". A minor example of this was Zappa's advice to his children about watching TV. Instead of taking statements at their face value, he said they should ask whether the person on TV got paid to say what they're saying. This principle was expressed by Hegel like this:Only when we discern that the content - the particular - is not self-subsistent, but derivative from something else, are its finitude and untruth shown in their proper light. (Logic §74)

Working at the other side of the world from Zappa, in Copenhagen and Paris, the painter Asger Jorn arrived at many similar positions to Zappa's. Although Zappa's attitudes and principles are unusual in rock and pop after the 60s - his disdain for conventional celebrity and beauty, his cynicism about the spectacle, his attack on normative values - they are central to artistic modernism in post-war Europe.

Critical of both American capitalism and Russian communism, Asger Jorn defined art as perpetual warfare on standardised thinking. In The Natural Order, a book he published in 1960 as the first "report" of the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism, he argued that positive science, by only trusting the majority of experimental results, and social democracy, by enforcing the will of the majority, both implied the extermination of minoritites. Zappa, too, was sensitive to the fascistic implications of normative liberal thought. Thing-Fish was written as a polemic in favour of the suppressed, the weird and the ugly. Both Jorn and Zappa emphasize the biological basis of human existence: sex and instinct rather than repressive reason.

Jorn turned the fact of man's animal nature into a criticism of Plato, and all the transcendent idealism which came in his wake. Unlike plants, Jorn argued, animals are oriented. Since they look for food, consume it through their mouths at the front and shit the waste product from their behinds, they face in a particular direction, and must decide which direction to move in.In French [Jorn said], "orientation" is called sens, like the English "sense". Meaning which is non-oriented has to be called non-sense. So the Platonic ideal of beauty, the symbol of perfect symmetry, the perfect sphere, is at the same time the definition of pure nonsense. (Peter Shield's Asger Jorn p. 132/Thoughts of an Artist 1966)

When Zappa put the statement "round things are ... boring" on Lumpy Gravy and put the same slogan on the One Size Fits All, he was expressing the same idea.

So, in conclusion, I want to say the phenomenology of One Size Fits All is dialectical and Hegelian: opposed to all fixed, metaphysical concepts which prevent human consciousness from fulfilling itself. This must explain why Zappa's work is so full of themes from such quintessentially German texts as Goethe's Faust and Thomas Mann's Doktor Faustus, neither of which he read: Zappa came from the same aesthetic and political orientation, one rarely to be found in American culture aside from its blues and funk musicians. The extraordinary way in which Zappa fulfilled the best hopes of the European avantgarde - with only the music of Stravinsky, Varèse and Webern as points of contact - is uncanny: a "coincidence" worthy of far more research than I have been able to give it.

Here's Asger Jorn's Décollage (1964) and some other deco collages of my own devise ...